When Games Go Hollywood

Maybe Video Game Adaptations Don't Have to be Bad?

Nerds are eating good these days. Over the past few months, TV adaptations of The Wheel of Time, Rings of Power, Sandman, and House of Dragons are streaming beloved storylines from high fantasy/scifi literature to living rooms across the world. Were that not enough, popular video game IPs are being adapted into some of the best shows going right now, notably in the form of Arcane: League of Legends and Cyberpunk: Edgerunners - both sitting at nearly perfect audience and critical scores on Rotten Tomatoes.

Such a unanimously positive reaction is nothing short of a miracle. I labeled all the above as being the realm of “nerds” because they are franchises that folks tend to “nerd out” about - in other words, they have deep and established fandoms. Fandom is a deep topic in the broader world of media studies, though most of what you need to know is that the word itself is derived from “fanatic.” Like Star Wars or Star Trek, there are pockets in these fandom that have read every scrap of lore or poured every frame of film - to them, it is basically (or literally) religion. This makes for some exhausting (and more often than not, “racist in the form of purists”) takes - a passionate fandom has the advantage of being a built-in audience for a given franchise, but one which is just as likely to love any new entrant as rip it apart piece by piece.

The success of Arcane, Edgerunners, and (arguably) shows like The Witcher is thus notable not only because they managed to thread the fandom needle better than their literature/comic-based brethren (and yes, I’m aware that The Witcher show is currently based on the books rather than the games, but let’s be real - we know why everyone is watching), but because they also overcame the fact that most shows or movies based on video games are dumpster fires.

What right do these shows have to be…good? It might be shockingly simple.

The Uneasy Relationship Between Hollywood and Video Games

Let’s begin with a bit of history via a quick tour of the Barcade on 24th Street in Manhattan (I’m sure my example holds true for other locations, this is merely the one I had spent some time at recently). Alongside quirks like Wizard of Wor and mainstays like Galaga, sits a game of somewhat more questionable reputation - Street Fighter: The Movie.

You know, the video game based on the movie which was based on the Street Fighter video games.

It’s an odd inclusion - there isn’t all that much redeemable about the game, aside from delivering a hefty dose of camp and nostalgia (we’ll ignore how many patrons can relate to a movie released in 1994). While it’s pretty fun to compel the legendary Raul Julia (RIP) into a “Psychocrusher,” what’s most notable about the game is how it near-perfectly represents the uneasy relationships between Hollywood and the gaming ecosystem.

The ongoing wisdom has generally been that movies based on games, and games based on movies, were almost always going to be bad (the issue with the game Street Fighter: The Movie might be that they crossed that bridge more than once). For movies or other media made into games there are a few bright spots, but the inverse was almost never true. The issue with so many Hollywood adaptations such as Street Fighter: The Movie, aside from sometimes being cocaine-fueled development boondoggles, is that they addressed the core story or concept from the games themselves in a cursory way, at best.

In some respects this is understandable as there isn’t always a lot of story to work with. Street Fighter II had characters with interrelated backstories, pieced together from a few cutscenes, but not a lot to unite them aside from the fact they all liked to pick fights. Technological limitations or otherwise left many early games without deep, engrossing stories. It could be argued that Hollywood has been in a position to fill in some blanks so that video game narratives could fit the mold of television or movie storytelling.

On the other hand, it could be just as convincingly argued that the problem is Hollywood not engaging with the source material it in a serious way. A number of more modern adaptations from video game franchises with deeper stories and lore than their early predecessors could muster, (Halo, Uncharted, Prince of Persia, etc.) are constructed in a way that the films or shows seem to be “inspired” by the games rather than using their narratives as a blueprint (the Halo showrunners made this point quite plainly). The result is a divisive product - fans of the games find little to attach themselves to the stories aside from references to a few characters or locations, whereas non-fans are subjected to a jumbled narrative.

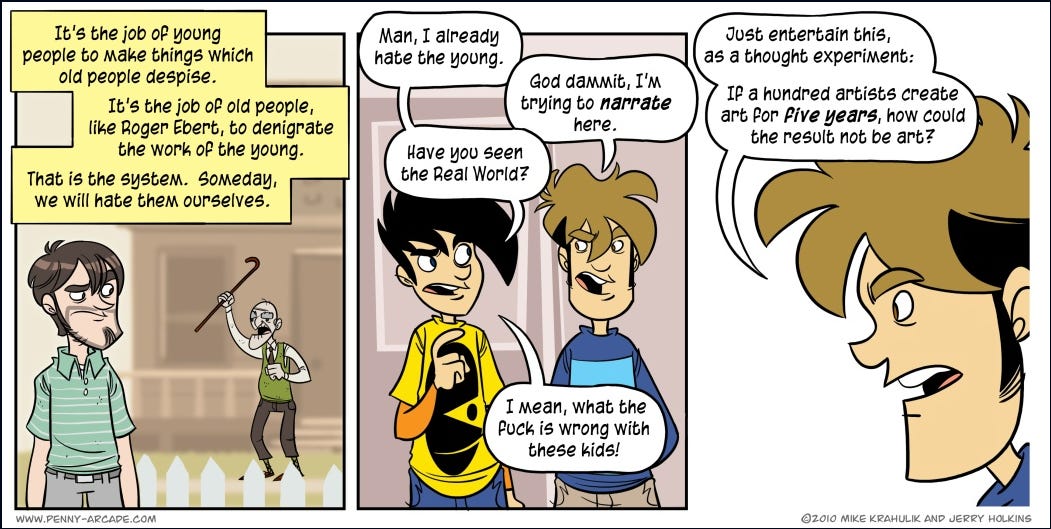

It’s hard not to believe that the latter view is the correct one, as video games have always been subject to “othering” from Hollywood - much of the early history of the games business is one that grew in the shadows of “mainstream” entertainment. This has resulted in a special kind of arrogant disdain of the artistry produced through the medium of games, exemplified by the likes of famed film critic Roger Ebert. (though the gaming community has not been entirely shy about punching back)

Engaging with the Worlds

As such, what is perhaps most significant about shows like Arcane, Edgerunner, and (again, arguably) The Witcher is not simply a shift towards intimate engagement with the fiction and mechanics of the game world, but how successful they have been because of how deeply they’ve engaged with core game materials. Arcane is basically a multi-part love letter around the “Legends” LOL players have engaged with for years. The Witcher weaves-in subtle details on screen, such as Geralt was using “signs” (limited, Witcher-specific magics) without a belabored explanation. More recently, Edgerunners carves innumerable details from the Night City of Cyberpunk: 2077, down to the actual player UI from the game experience. These shows reward viewers with a deeper knowledge of the game by reveling in the small details, while managing to create compelling narrative precisely because they respect and leverage the fiction of the game rather than using it as a thin coat of paint over a “made-for-TV/movie” story.

More simply, some of the best video game adaptations on TV are being made right now as some of the best stories in video games are also being made right now, and Hollywood is either left with fewer hotels to fill or recognizing that catering to the fans of these franchises can be profitable. Whether it is the scale of the audience, a desire to cash in on an established fan base, or showrunners who are increasingly of a generation which is more familiar with the medium of video gaming, Hollywood is more bullish on gaming than ever - over 40 projects are currently in some stage of development.

The payoff for both sectors is clear. Aside from broader cultural recognition, games like The Witcher (at the time, a dated game) and Cyberpunk: 2077 (less dated, but also recently updated) experienced sizeable spikes in player activity for the same reason that Hollywood may continue to find video game franchises successful projects - fans tend to enjoy transmedia storytelling. The potential for this type of storytelling is one of the more potent, if not yet fully realized, strategies from Netflix’s foray into gaming. The fact that all the examples noted above (and other excellent adaptations, such as Castlevania) are available through Netflix is probably not a coincidence.

Gaming has always been big business, but as game fans permeate every spectrum and age group of the consumer market we’ll find a larger number of businesses beyond game development who want to tap into this market. Adult consumers now have familiarity and affinity for franchises they group up with, like Sonic the Hedgehog, in a manner not entirely unlike various Disney characters with generations before. Whether it be marketing, showrunning, or building non-gaming specific worlds, the prevailing methodology should be what we can learn-from rather than impose-upon consumer orientations towards gaming.

This all amounts to a vindication of sorts for game fans “nerding out,” as those who have not had a deep engagement with the gaming are learning what game fans have known for years - despite the occasional fits of scorn from mainstream media, video games contain compelling stories, characters, and settings that stand up even without interactivity. Hollywood might have taken a few tries to get it right, but we may be at the onset of a fundamental reconfiguration of broader entertainment consumption where interactive and passive entertainment experiences exist hand-in-hand, and the interactive IPs are playing the leading role in these relationships.

The power of gaming IP means that understanding gaming is more important than ever. Business decision makers can get a foundational perspective from my new book, Get in the Game: How to Level Up Your Business with Gaming, Esports, and Emerging Technologies. Consider picking up a copy.